It is National Adoption Month, and I’m remembering the four adoptions that I oversaw in my five years as a foster care social worker. These were among the happiest occasions in my child welfare career.

What could be better than seeing a child who had been abused or neglected permanently united with a family that had already proven their love and nurturance by fostering?

But I’m also remembering the adoptions that did not happen, despite the fact that they were clearly in the best interests of the children. Because the system too blindly favors biological parents, the interests of the children and their future prospects took a back seat.

“Tamara” came into care at the age of two when her mother was arrested for hitting and knocking her down at a CVS. After two years in foster care, Tamara was totally bonded to her foster family.

Despite months of individual and family therapy and parenting training, Tamara’s mother had not developed an attachment to her. She was unable to state anything she liked about Tamara, a lively, bubbly child.

In a court-ordered bonding study, knowing she was being observed, Tamara’s mother was unresponsive to Tamara’s attempts to get a reaction to her drawing. The parenting counselor who had worked with Tamara and her mother agreed with the bonding study: Tamara’s mother just was not attached to her.

Unfortunately, the judge did not agree. The government attorney and I were nearly in tears as we tried to explain the type of nurturing that children need for healthy development. All he saw was that Tamara’s mother had followed the court’s orders, such as participating in therapy and parenting training.

It did not matter that these services had not worked to make her a better parent. I had to return Tamara to her mother.

Then there was Davon. His extremely nurturing foster parents, a married couple with grown children, brought him up from the time that his mother abandoned him at the age of 3 months until past his second birthday.

In the foster home, Davon basked in an atmosphere of love, order and intellectual stimulation. But then, his mother named the real father, who had not known of Davon’s existence.

The 19-year-old father, jobless and a high school dropout, wanted to bring up his son. He had not abused or neglected Davon. Nevertheless, it was clear that Davon would do better with his foster parents.

I left the job before I would have had the sad task of removing Davon from the only home he remembered. But I later heard from his attorney, who had opposed the move, that she had serious concerns about his emotional and intellectual development in the somewhat chaotic home to which he was transplanted.

I’ve been reading Meghan Walbert’s Foster Parent Diary in the New York Times. For seven months, she and her husband have fostered “Blue-Jay,” who came to their home at the age of three. Through her blog, we see a fearful child gradually settling in to the family.

We read about Blue-Jay’s anguish after his birth parents tell him on a visit that he is coming “home.” “I don’t want to live in a different house. I want to live in this house with this family,” he wails.

We see him becoming afraid of new places and new people, for fear that he will be taken away. How long this limbo will last is anybody’s guess.

The problem is, as Elizabeth Bartholet of Harvard Law School puts it, that the child welfare system puts parents’ rights ahead of the rights of the child. But laws are not the whole problem. District of Columbia law allows for a child to be adopted against a parent’s consent if it is in the child’s best interests. But courts will generally not waive a parent’s right to consent if the parent has complied with court orders or, as in the case of Davon’s father, was not guilty of abuse or neglect.

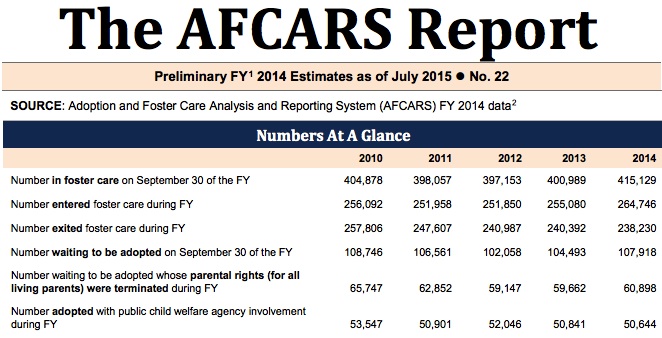

Federal law was changed in 1997 to require that the government move to terminate parental rights if a child has been in foster care 15 out of the most recent 22 months. But even after the government moves for termination, it can take a year or more before an adoption is finalized.

During that time parents can continue to press for reunification, a father can appear, or a relative can be found who is given priority because of the blood relationship. In the meantime, some children will become more bonded to foster and adoptive families, making the separation even more harmful.

Accumulating research findings show how important it is for a child to have a loving, consistent, responsive caregiver. Caregiver-child interactions shape the developing brain. Loving and appropriate responses to the child’s cries, gestures, and early speech are necessary for the child’s physical, mental and emotional health.

I hope that our increasing knowledge about early childhood brain development will eventually lead to a change in practice that puts the best interests of children at the heart of child welfare and allows for many more joyful adoption days in the future.

This column was published in the Chronicle of Social Change on November 23, 2015.