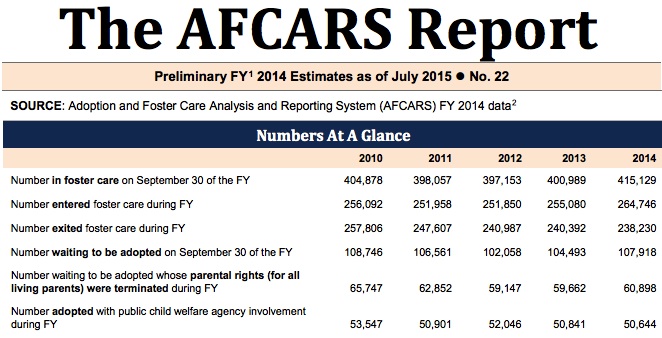

The federal government issued its new foster care data report on Sept. 18, and the news was startling. Foster care caseloads were up substantially for the first time in a decade. Between 2013 and 2014, the number of children in foster care increased from 400,989 to 415,129, which is an increase of 3.5 percent. This was the second consecutive increase in foster care caseloads.

The new data appear to confirm an end to the major decline in caseloads that occurred in the first decade of this century. The number of children in foster care fell from 567,000 in 1999 to 398,000 in 2011. The foster care caseloads declined slightly in 2012 and increased slightly in 2013, to 400,989. The 2014 figure suggests that we may be entering an era of increasing foster care caseloads.

Increased entries into foster care appeared to account for most of the increase in caseloads. The number entering foster care increased by almost 10,000 over the year. The number exiting foster care decreased, but by a much smaller amount.

The increase in foster care caseloads cannot be accounted for by expansion of some foster care systems to include youth between the ages of 18 and 21. The age distribution of children in foster care remained almost the same over the last year, as did the age at entry into foster care and exit from foster care.

The Department of Health and Human Services did not offer an explanation of this increase. However, several factors have been cited as explanations for increases at the state and local levels. Reports from many states suggest that the increased popularity of drugs like heroin and methamphetamine are resulting in more kids being removed from their families. For example, the number of children in foster care in Kansas has reached an all-time high, whichprofessionals attributed at least in part to the revival of heroin and methamphetamine.

Changes in child welfare policy may be responsible for caseload increases in some states. The number of children in foster care in Florida reached its highest level since 2008 this July. Among the reasons given are the use of a new method for assessing risks to a child’s safety, which is resulting in more removals. The state shifted to this system after a widely publicized series of child deaths. A similar dynamic is occurring in Oklahoma, where a spate of child deaths resulted in an increase in removals and foster care caseloads.

The number of youth in foster care has risen for two consecutive years, according to federal data collected from states

The Florida and Oklahoma situations illustrate the cyclical nature of child welfare practice. Child welfare systems have to balance the harm caused by removing children from their families with the risks incurred by leaving them in possibly dangerous situations. Many states have been reducing their caseloads for years. After years of erring on the side of keeping children at home, they may be reconsidering in light of evidence that they have gone too far.

There is a limit to how much a state can safely reduce its rate of child removals. I was a social worker in the District of Columbia between 2010 and 2014, when the caseload was cut in half. While this reduction was occurring, I heard from many attorneys working in the system that children were being kept in toxic homes for too long and were more troubled when they were finally removed.

Many professionals involved with the District’s child welfare system during the time of caseload reduction also expressed fear of a tragedy due to children being left in an unsafe home. One such event did occur. As I described in an earlier column, a child whose family had been the target of an investigation but who was not removed later disappeared and is presumed dead.

It is possible that increased investment in services to families will make possible a resumption in the decline in child removals without compromising child safety. Congress is considering a major change in child welfare funding so that services to prevent foster care placement could be funded at the same level as out-of-home care.

Perhaps if such a policy is implemented, it will usher in a new era of caseload decline, based on a foundation of adequate monitoring and services to families that have come to the attention of the system. Let us hope that it does not lead to financial pressure to keep kids at home even when they are not safe.

This column was published in the Chronicle of Social Change on October 5, 2015

No comments:

Post a Comment